a blog about programming

Reagent Mysteries

Part 1: Vectors and Sequences

published Dec 26, 2016

Reagent is a popular, practical ClojureScript wrapper for React. Its popularity is easily explained. It uses hiccup syntax as an elegant way to describe a DOM tree as a hierarchy of React components, where each component is a simple ClojureScript function. Furthermore, to aid tracking the efficient re-rendering of scenes, it introduces ratoms as an extension of Clojure’s atom abstraction, a powerful addition to React’s props mechanism.

At the same time, Reagent is practical in that, wherever its model is too restrictive, it gives the programmer the escape hatches and efficiency hacks necessary to build fast real-world applications.

Reagent is some magical features, but does that make it mysterious? It’s true that its abstractions, while useful and often conductive to cleaner code, can sometimes also be leaky. As a result, knowledge of the implementation is helpful to figure out how things work. In this series of blog posts, I will attempt to dispel the air of mystery surrounding Reagent by explaining its underlying concepts.

Building a table

This first focuses on the example of building an HTML table with Reagent. React requires tables to be properly structured, including thead and tbody elements, so we know what the hiccup representation of the DOM should look like:

[:table

[:thead

[:tr

[:th "name"] [:th "country"] [:th "date"]]]

[:tbody

[:tr

[:td "Descartes"] [:td "France"] [:td "1596"]]

[:tr

;; ...

]]]In good Clojure tradition, we start with a data structure:

(def philosopher-cols

[:name :country :date])

(def philosophers

[{:name "Descartes" :country "France" :date 1596}

{:name "Kant" :country "Prussia" :date 1724}

{:name "Quine" :country "U.S.A." :date 1908}])Each row is a map of attribute to value. Because we chose a common format, we can print this structure straight away in the cljs REPL using clojure.core/print-table:

example.table=> (clojure.pprint/print-table philosopher-cols philosophers)

| :name | :country | :date |

|-----------+----------+-------|

| Descartes | France | 1596 |

| Kant | Prussia | 1724 |

| Quine | U.S.A. | 1908 |Next, we can build a component that takes the same arguments as print-table:

(defn table-ui [cols rel]

[:table

[:thead

[:tr (map (fn [col] [:th {:key col} (name col)]) cols)]]

[:tbody

(map (partial row-ui cols) rel)]])The -ui suffix is a hint that we’re dealing with a render function. The render function for individual rows is simple:

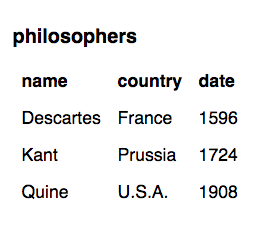

(defn row-ui [cols m]

[:tr {:key (:name m)} (map (fn [col] [:td {:key col} (get m col)]) cols)])Voila, we can see the result in the browser:

Lists and keys

You may have noticed that row-ui attaches a key prop to

the tr element. Although this uses the normal syntax for attaching DOM

attributes like style, the key attribute has

special meaning. React’s diffing algorithm uses this attribute as a

hint to reidentify an element during a re-render operation. In any list

or table, each child needs to have a key unique in its context. In

essence, you need to pick a primary key for your collection.

In practical terms, you can leave out list keys during the exploration phase. Everything will work, except that you will see warnings in your browser console. Reagent will complain:

Warning: Every element in a seq should have a unique :key: ([:th “name”] [:th “country”] [:th “date”]) (in example.reagent.root > example.reagent.table_ui)

and so will React:

Warning: Each child in an array or iterator should have a unique “key” prop. Check the render method of

example.reagent.table_ui. See https://fb.me/react-warning-keys for more information. in th (created by example.reagent.table_ui) in example.reagent.table_ui (created by example.reagent.root) in div (created by example.reagent.root) in example.reagent.root

If you see these messages, you know it’s time to assign each

tr, td or li a key (normally a

keyword, string or number).

Vectors and sequences

So much for the code, but how does it work? Reagent adds to React the convenience of expressing components as simple ClojureScript functions. As table-ui has no state, it consists only of a render function. In Reagent-speak this is a Form-1 Component.

When the component is rendered, the hiccup structure returned by the cljs function is converted into a hierarchy of React elements, React’s internal representation of the DOM. To see how what exactly Reagent sees, we can call the function from the REPL. Here’s what it returns:

[:table

[:thead

[:tr

([:th {:key :name} "name"]

[:th {:key :country} "country"]

[:th {:key :date} "date"])]]

[:tbody

([:tr

{:key "Descartes"}

([:td {:key :name} "Descartes"]

[:td {:key :country} "France"]

[:td {:key :date} 1596])]

[:tr

{:key "Kant"}

([:td {:key :name} "Kant"]

[:td {:key :country} "Prussia"]

[:td {:key :date} 1724])]

; ...

)]]Notice that this is not quite the same as what we intended initially. Compare the header to our draft above:

[:thead

[:tr [:th "name"] [:th "country"] [:th "date"]]]The generated markup is wrapped in a pair of parentheses, which in Clojure signifies a sequence (or list, which has similar properties). A quick look at the code explains this easily: map returns a single value, a sequence. We could modify table-ui to build the intended markup explicitly:

[:thead

(into [:tr]

(map (fn [col] [:th {:key col} (name col)]) cols))]And yet, our initial, more concise attempt works. Why?

The answer is that Reagent (and before it, hiccup) anticipates this usage and, in the course of transforming hiccup syntax to React elements, automatically expands non-vector sequences into the enclosing elements.

This also means that row-ui does not actually function as a React component; it is evaluated and its result spliced into the tbody element.

Gotchas

This is a convenient shortcut, but like many conveniences, there’s a price. First, in Clojure vectors implement the sequence interface, and a vector can often be exchanged transparently in place of sequences and vice versa. But here you need to keep in mind that Reagent confers to vectors (but not to sequences) the special significance of representing components or DOM elements.

So converting the result to a vector breaks rendering:

;; This won't work as expected:

[:thead

[:tr (vec (map (fn [col] [:th {:key col} (name col)]) cols))]]Reagent will try to interpret a vector of vectors as a component but a vector is neither a keyword nor a render function (the only valid component specifiers).

The second gotcha is that, while into explicitly

realizes the lazy sequence, leaving the sequence unrealized is dangerous

when you rely on ratoms being dereferenced in the course of its

realization. The effect of this issue is that everything will seem to

work, but the component will not be re-rendered when the state

changes.

Fortunately the fix is simply to wrap the map (or

for) call in doallto force its realization

before the render function returns:

[:thead

[:tr (doall (map (fn [col] [:th {:key col} (name col)]) cols))]]Personally I recommend using into over relying on

doall for child sequences because into makes

it obvious what hierarchy is being generated, and explicit is better than

implict.

Happily, there’s also a non-gotcha to report. Suppose you want to hide some philosophers, based on their date of birth. A convenient shortcut is simply to return nil for rows to be ignored:

(defn row-ui [cols m]

(when (>= date 1900)

[:tr {:key (:name m)} (map (fn [col] [:td {:key col} (get m col)]) cols)]))The upshot is that Reagent is a good sport and will ignore any child elements that evaluate to nil, a feature that is turns out to be useful in building UIs. The exception to this is when Reagent tries to interpret a vector whose first element is nil; in this case it will try to call nil, with a predictable result.

Further Reading

Click here for part two of this series. The full source of this example is available here.

This is presumably for side-effects, a blog by Paulus Esterhazy. Don't forget to say hello on twitter or by email